Understanding State Machines

A “state machine” represents a conceptual approach to how a program operates: it maintains a “state” and modifies this state in response to specific “transactions.” In a “replicated state machine,” the duty and accountability for managing this evolving state are distributed across several computers, offering fault tolerance. Hedera enables a replicated state machine. Numerous nodes, even potentially opposing ones, can consistently maintain the state of a dataset. For example, the HBAR quantity across a group of accounts. As detailed earlier, transactions are submitted to the network, and subsequently, the hashgraph algorithm assigns them a consensus timestamp and a position in the consensus sequence. Once all nodes reach an agreement on the transaction sequence, they sequentially apply them to the state. This procedure ensures each node’s state copy remains consistent. Every node applies (for example, adjusts the payer & recipient balances for an HBAR payment) the transactions to the state following the mutually agreed sequence, thus preserving a uniform state with other nodes at any specific moment.

State vs. History

The latest state (e.g., the HBAR balances of each account) and the history of the transactions that altered that state are two distinct data structures with different properties. State is mutable by definition, constantly changing as transactions are applied to it. In contrast, the history of transactions is generally considered immutable and irreversible. State and history present very different storage burdens. At the high throughput that Hedera can support, history will grow very quickly, increasing the burden of storing it. State will also grow as new accounts, files, and smart contracts are created, but at a slower pace.Roles of Distributed Technology (DLT) Node

There are three mostly independent functions that a distributed ledger technology (DLT) node can perform:- Contribute to consensus

- Persist history of transactions

- Persist state

Priorities of Hedera Mainnet Nodes

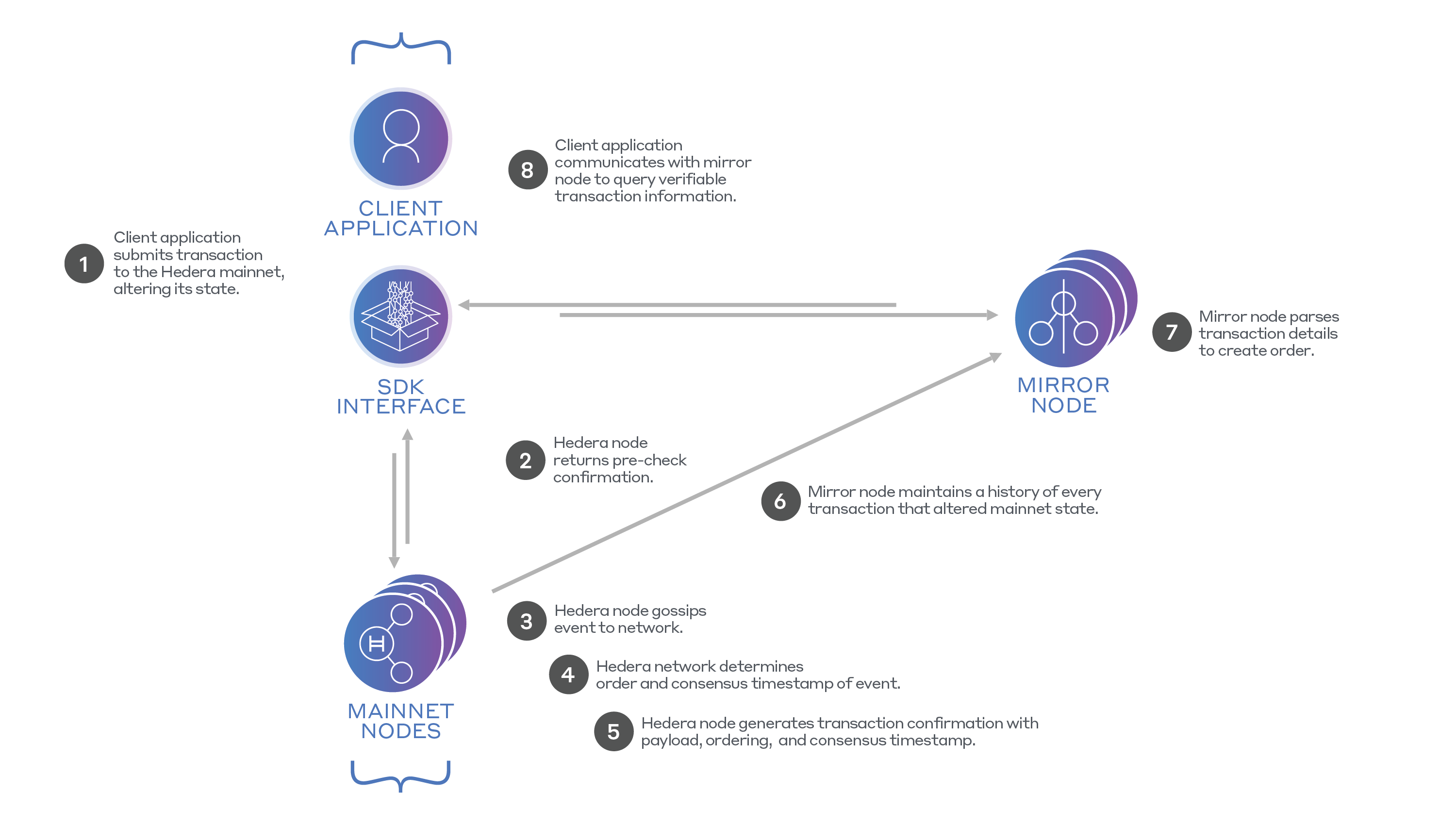

For Hedera Mainnet nodes, the priorities contribute to consensus and persists state. The hashgraph, which contains all the transactions that change the state, is constantly pruned after transactions are assigned a place in consensus order. Mainnet nodes can delete older portions of the hashgraph because the algorithm delivers finality – once a transaction has been assigned a timestamp, ordered, and then applied to the state, there is no chance of reversal. Consequently, there is no need to keep historical transactions around in case they might be necessary to apply them in a different order. To prevent such historical transactions from filling up the node’s storage, mainnet nodes delete historical transactions. But there is value in the history being persisted, even if not by mainnet nodes. An auditor might want to determine the identities of the parties that sent HBAR to a given account or the times of those transfers, neither of which would be available from the state (e.g., the balances of the accounts) alone.Roles of Mirror Nodes

Mirror nodes in the Hedera architecture, in addition to maintaining state, can also store transaction history. A particular mirror can choose whether to store all history, no history, or possibly only a fraction of the history, perhaps only for particular transaction types, particular accounts, etc. In addition to the history, mirror nodes store information that allows them to prove that their history is correct, even for some kinds of partial histories. This prevents a malicious mirror node from lying about what it is storing. A client seeking a transaction from the past would query an appropriate mirror for the record of that transaction. As the burden of storing history is borne by mirrors and not mainnet nodes, the latter can be optimized for the more fundamental role of consensus and state storage.FAQ

What is the concept of <code>state</code> in the Hedera Network?

What is the concept of <code>state</code> in the Hedera Network?

The state in the Hedera Network is the current status of all data, like the amount of HBAR in a set of accounts. It is maintained across multiple nodes in a consistent representation, providing fault tolerance. The state constantly changes as transactions are applied to it.

How does Hedera handle history?

How does Hedera handle history?

The history of transactions is maintained as a separate data structure from the state. It provides a record of transactions that have changed the state over time. It is usually envisaged as immutable and irreversible. Mirror nodes in the Hedera architecture store the transaction history, while mainnet nodes focus on consensus and state storage.

What are the roles of mainnet nodes and mirror nodes?

What are the roles of mainnet nodes and mirror nodes?

Mainnet nodes prioritize contributing to consensus and persisting state. They delete historical transactions after they are assigned a place in the consensus order. Mirror nodes, on the other hand, store the transaction history and maintain state, providing a record of past transactions for audit purposes.